主講:Larissa Heinrich(美國加州大學柏克萊分校博士班學生)

時間:一九九七年十一月十五日(星期六)下午二時至四時

地點:中央研究院歷史語言研究所研究大樓701室(圓桌會議室)

‘Influence’ is a curse of art criticism primarily because of its wrong-headed grammatical prejudice about who is the agent and who the patient: it seems to reverse the active/passive relation which the historical actor experiences and the inferential beholder will wish to take into account. If one says that X influenced Y it dies seems that one is saying that X did something to Y rather than that Y did something to X. But in the consideration of good picture and painters the second is always the more lively reality.

–Michael Baxandall, Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures

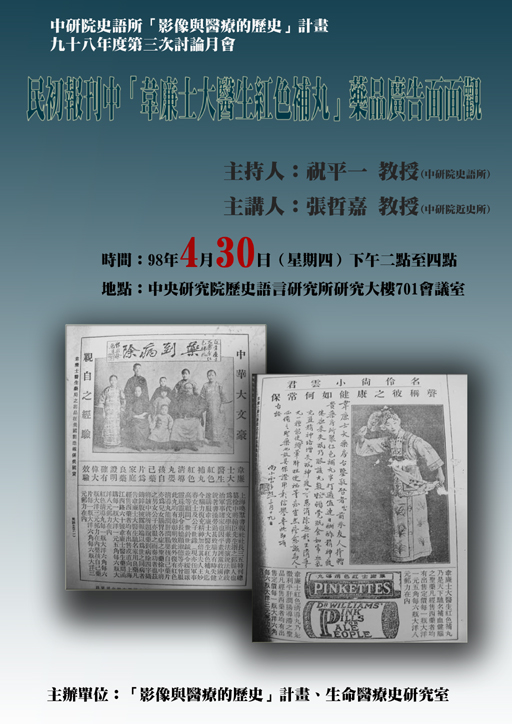

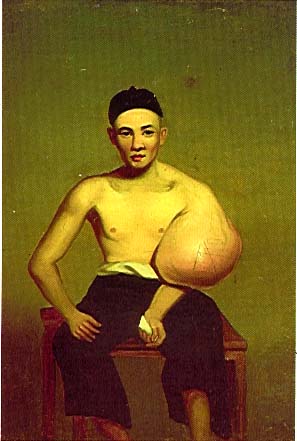

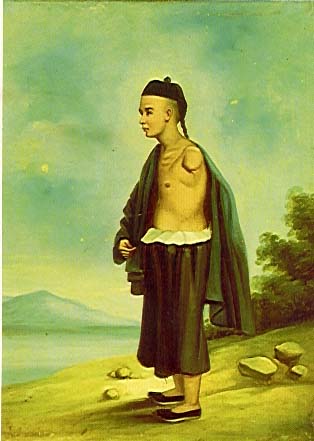

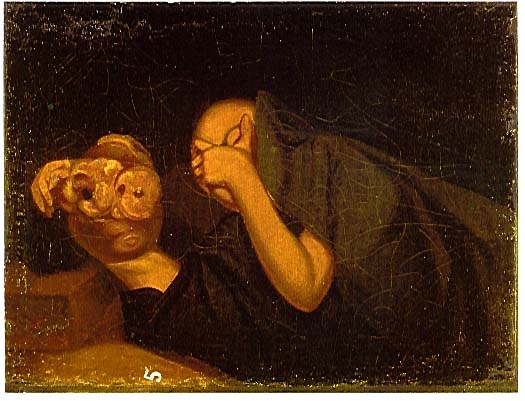

In the century and a half since Lam Qua made the disturbing series of medical portraits that accompanied Reverend Peter Parker on his fund-gathering mission to medical schools and Protestant authorities in the West, the paintings have only been exhibited once. Curators shy away from their grotesque, unflinching portrayal of cysts, tumors, growths and amputations juxtaposed with perplexingly serene human hosts: too unsettling, too “inappropriate for public view.” Likewise evaluations of Lam Qua for the most part concentrate on his mastery of port-scenes and commercial portraiture, only mentioning his medical portraits as a sort of curious afterthought, despite the fact that they represent the largest unified body of extant works by the artist (86 pieces are in the collection of Yale Medical College Library; another smaller group is at Guy’s Medical Hospital in London; and four paintings are housed at Cornell).

Yet precisely because of their medical content and the complexity of inter-related field they bring together (are they portraits? medical illustrations? simple works of art? innovative? Chinese or Western?), this set of paintings is a uniquely valuable resource for research on the beginnings of modernity in China, and in particular, on changing attitdes toward the self during this time. Firstly, as medical illustration their subject matter is not limited to either the elite literati of Chinese painting nor to the wealthy hong merchants and foreign traders of typical commercial portraiture. Thus through then we have a rare opportunity to view representations of a range of classes and gender spanning from the poorest, uneducated servant to the wealthiest urban matron. Secondly, since in their capacity as medical illustrations the paintings were intended to accompany or illuminate a more discursive representation of illness, we may “read” the paintings in conjunction with their detailed textual counterpart — Parker’s case-journal — allowing us to attempt a level of evaluation not possible with typical, undocumented portraiture. Finally, because these paintings were intended for use essentially as a kind of propaganda for the medical mission in China, they offer a valuable opportunity to look at how Westerners and Chinese might have conceived of — and attempted to shape — the Chinese self on the eve of the Opium War, when the balance of power concerning the development of “modernity” shifted decidedly westward. In short, Lam Qua’s medical portraiture is valuable as an ideological resource concerning visions of the newly emerging modern Chinese self.

In this paper I attempt to provide a basic analysis of some of what I feel are Lam Qua’s more representative works of medical portraiture, focusing in the visual contribution to the invention of the stereotype of the “Sick man of China.” How did Lam Qua conceive of and create sickness and Chinese identity in his painting? How did he interpret the specific ideologies that Peter Parker called for in his intended use of the paintings? Barbara Stafford makes the point via Foucault that the very fact of making specific visual records of externally manifest ailment like “blisters, blotches, eruptions, and tumors” was part of a uniquely modern obsession with cataloguing the “disfigurements punctuating the modern process of visualization get translated in a Chinese setting? Were there precedents for this kind of representation in China? And moving forward along the historical spectrum, how might these paintings have influenced or anticipated the way pathology and Chinese identity were interpreted after the Opium War, when Western medicine became an even more powerful vehicle for intellectual colonialism?

—

I begin by looking briefly at a few examples of medical-illustration series produced in China that pre-date Lam Qua’s series but still share certain features with it. While it is impossible to establish a conclusive link between these illustrations and Lam Qua’s, nonetheless their organization as the circumstances of their production suggest that Lam Qua’s unique contribution to medical illustration was not an historical accident, as has something’s been suggested. In the main body of the paper I analyze a selection of the Lam Qua uses composition and content to transmit a message about the “curability” of Chinese culture, simultaneously fashioning a Chinese culture that is “sick” while at the same time providing a cure for it, all in keeping with the propagandistic requirements of Parker’s missionary ideology. Finally I look at another fascinating series of medical illustrations from the first decades of the 20th-century, a time when (as Andrews puts it) medical missionaries began to have a more “significant impact on literate Chinese physicians.” Here I compare photographs taken by medical missionaries in Maxwell’s Diseases of China with Lam Qua’s portraiture, and suggest that the association of sickness with Chineseness in general and the Chinese body in specific had, by the time of the photographs, moved from being based in an abstract notion of “culture” to being based in a highly concrete, post-Darwinian concept of race. I conclude that Lam Qua’s paintings, like the Lu Xun fiction which came later, conflate illness with Chinese identity, but in a way that is deeply idealistic, “curable” in effect, and therefore in telling contrast to the more divided notions of the self that appeared as Western medicine and ideoligy in general began to take a stronger hold.

PO ASHING (Before and after surgery), by Lam Qua

Patient of Peter Parker, by Lam Qua

This study is rumination on that it meant to be and to become the “Sick Man of China.” Though the lense of a medical portraitist trained in the Western style in the early in 1800’s, it looks at notions of self in a time when Western medicine had not yet fully matured to its role of providing a pretext for claims of Western cultural superiority. Paralleling the development of literary tropes of the time, it hypothesizes a gradual “medicalization” of the self, beginning with early representations of more anonymous sick bodies, moving to Lam Qua’s idealization portrayal of a “curable” self, and culminating in the ethics of the Eugenics movement and the total conflation of cultural identity with illness exemplified by medical photography in China of the early 20th century.

(Abbreviated introduction. Article to be published in the antholigy “Translating Modernity, ed. Lydia Liu. Please contact the author, Larissa Heinrich, c/o Department of East Asian Languages, Durant Hall, Universuty of Califormia at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA)